Why we use different alpha values (α) for alloys when measuring resistance at 20 °C ?

Resistance changes with temperature. The temperature coefficient of resistance — commonly called alpha (α) — quantifies how much a material’s resistance changes per degree Celsius around a chosen reference temperature (commonly 20 °C). Different pure metals and alloys have different electronic structures, impurity levels and microstructures, so their α values differ — and alloys are often chosen specifically because they reduce or tailor α (for stability, shunts, precision resistors, or sensor design). Standards and measurement practice define a common reference temperature (20 °C) so everyone reports and compares resistance consistently.

1. What is α (the temperature coefficient of resistance)?

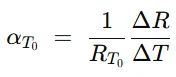

Formally, the temperature coefficient of resistance (TCR) or α is defined (for small temperature ranges) as the fractional change in resistance per degree Celsius:

So if R20 is the resistance at the reference temperature 20 °C, and the temperature rises by ΔT, the approximate new resistance is:

RT ≈ R20(1+α20 (T−20))

Alpha (α) is usually quoted in units of 1/°C (or more practically in parts-per-million per °C — ppm/°C). For many conductors α is positive (resistance rises with temperature); for some materials (certain semiconductors) it’s negative.

2. Why measure / report resistance at a reference temperature?

Resistance is temperature dependent. If everybody measured “resistance” at whatever temperature happened to be in their shop, comparisons would be meaningless. Standards therefore require a reference temperature so that resistance values are comparable and calibrations reproducible.

Historically and internationally, 20 °C emerged as the practical, widely adopted reference temperature used for many physical standards (including dimensional metrology and many electrical properties). ISO and national metrology bodies document the use of 20 °C as a standard reference temperature; NIST and other authorities also explain the historical and practical reasons for the choice. Using a single reference temperature simplifies reporting, calibration, and temperature compensation.

3. Why do different materials have different α values?

Alpha depends on the microscopic physics of conduction in the material:

- Pure metals (e.g., copper, silver, aluminum): conduction is via free electrons scattered by lattice vibrations (phonons). As temperature increases, phonon population increases, scattering increases and resistivity rises. For many common metals alpha (α) is around 0.003–0.006 /°C at 20 °C (that is, resistance increases by ~0.3–0.6% per 100 °C). Typical reported values include copper ≈ 0.00386–0.00393 /°C and aluminum ≈ 0.0043 /°C.

- Magnetic and transition metals (e.g., iron, nickel): have larger alpha (α) because electron scattering mechanisms and magnetic effects cause stronger temperature dependence.

- Alloys (e.g., constantan, manganin, nichrome): alloys are mixtures of metals with different electron scattering behaviors and complex microstructures. The presence of alloying elements and defects introduces temperature-dependent scattering that can compensate the phonon scattering. By appropriate composition and processing, the net change of resistivity with temperature can be reduced or even made nearly zero over a chosen temperature range. That’s why certain alloys have very low(in ppm) or near-zero alpha(α) — they are used where a stable resistance with temperature is required for example : Standard resistance Boxes which are used for calibration of resistance meters

In short: different electronic scattering mechanisms and microstructures ⇒ different α.

4. Examples — α of common metals and alloys (at ~20 °C)

Below are representative α values commonly used in industry references (note: α can vary somewhat with impurity, cold-work, annealing and exact composition):

- Copper (annealed): ≈ 0.00386–0.00393 /°C. Copper is the default conductor for power/cable work; its α is relatively well known and is used for temperature compensation and correction in low-resistance measurement.

- Aluminium: ≈ 0.0042–0.0043 /°C. Slightly higher TCR than copper.

- Silver: ≈ 0.0038 /°C (silver’s resistivity lower than copper but α similar).

- Iron / Nickel: larger α (iron ≈ 0.0065 /°C).

Alloys used for low TCR or stable resistance:

- Manganin (Cu–Mn–Ni alloy): α can be extremely small (on the order of parts-per-million per °C around room temperature) — often quoted near 0 ppm/°C for a chosen temperature. Manganin is widely used for precision shunts and reference resistors because it combines low TCR, good long-term stability and low thermal EMF against copper.

- Constantan (Cu–Ni ~55/45): near-zero or small negative TCR depending on composition and temperature range. Commonly used for thermocouple legs (type E and J) and precision resistors.

- Nichrome (Ni–Cr): used for heating elements; α is relatively low compared to pure nickel but not zero — chosen for high resistivity and reasonable stability at elevated temperatures.

These values are widely tabulated in handbooks and standards; engineers choose materials depending on whether a large predictable α (for sensors) or a very small α (for precision resistors/shunts) is desired.

5. Why alloys? — Practical reasons for using different α alloys

Different applications require different temperature behaviours:

- Precision resistors and laboratory standards: want resistors whose resistance does not change with normal environmental temperature swings. Manganin and selected nickel–chromium alloys are favoured because they minimize drift with temperature (low α) and have predictable long-term behaviour. This reduces the need for temperature control and simplifies uncertainty budgets.

- Shunts for high current measurement: shunts must have stable resistance under heating and over time. Alloys with low TCR and good mechanical stability (e.g., manganin, selected Cu-Ni blends) keep measurement errors small as the shunt warms during operation.

- Heating elements / resistive sensors (RTDs): here you want a predictable and reproducible α — platinum (Pt) is the gold-standard for RTDs because its R–T curve is stable and reproducible internationally (IEC 60751 / Pt100 family). Platinum’s α (and higher-order polynomial coefficients) are well characterized so it can serve as a calibrated temperature sensor.

- Thermocouple alloys / compensation leads: certain alloys (constantan etc.) are chosen to produce stable thermoelectric behavior and predictable TCR where needed.

In other words: select material to match the role — either to minimize α (stability) or to make α large and predictable (sensing).

6. Standards and measurement practice: why 20 °C and which standards to look at

A few standards and practice documents relevant to resistance, resistivity and temperature compensation:

- ISO 1 (Standard reference temperature 20 °C): ISO documents the adoption of 20 °C as a reference for industrial measurements — primarily for dimensional metrology, but the choice propagated into many engineering practices as a convenient lab ambient temperature.

- ASTM standards (e.g., ASTM B193, others): many ASTM procedures for measuring conductivity/resistivity reference 20 °C and give recommended α values (e.g., copper α ≈ 0.00393 at 20 °C). ASTM test methods provide procedures for determining resistivity and reporting at a reference temperature.

- IEC / EN standards for RTDs (IEC 60751 / EN 60751): define the relationship between resistance and temperature for platinum resistance thermometers (Pt100 etc.), polynomial coefficients and tolerance classes. These are standards where α and higher-order coefficients are central to sensor performance and interchangeability.

- IEC 60468 / ISO methods for resistivity: procedures for measuring resistivity of conductor materials, giving both reference and routine methods — important when reporting resistivity at a defined temperature.

- Indian Standards (example): IS 3636 (test methods for temperature coefficient) and other BIS documents provide national methods for measuring and reporting TCR in the Indian context. If you are publishing technical material on Maxwell India, referring to relevant IS documents helps local readers.

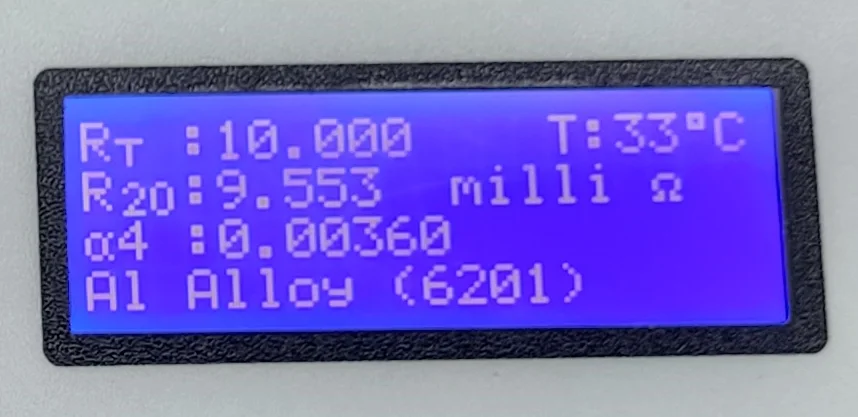

When calibrating or publishing resistance values, labs commonly measure the ambient or part temperature with a calibrated thermometer or RTD and report resistances corrected to R at 20 °C (or whatever reference the standard requires). Instruments like low-resistance ohmmeters commonly implement automatic temperature compensation (ATC) to convert measured resistance at the current ambient to the equivalent at 20 °C using a chosen α (often copper for conductor testing).

7. Why 20 °C specifically? (history + practical reasons)

Why 20 °C and not 0 °C or 25 °C? A short summary:

- Historical international agreement: metrology committees settled on 20 °C as a practical compromise reference temperature (NIST and CIPM discussions in the early 20th century). 20 °C is neither too cold nor too warm for typical laboratory environments worldwide.

- Practical lab conditions: many labs operate near 20–23 °C; selecting 20 °C simplifies heating/cooling requirements for calibration compared with 0 °C while being closer to the most common ambient temperature than 25 °C in some climates.

- Cross-domain alignment: using the same reference as dimensional metrology and other standards simplifies documentation and calibration procedures across disciplines.

Because of these reasons, many electrical reference procedures and manufacturer datasheets give resistances and α values referenced to 20 °C, or provide conversion formulas to/from 20 °C

8. How to apply α in measurement and the pitfalls

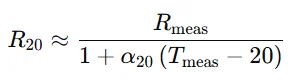

Correcting a measured resistance to 20 °C:

If you measure Rmeas at measured temperature Tmeas, and know α at 20 °C, you calculate:

Here are alpha (α) values for various Copper and Aluminium alloys:

| Alpha (α) Values | Material |

| 0.00270 | Copper Mg 0.5% Alloy |

| 0.00310 | Cu Cd/Mg 0.2% Alloy |

| 0.00320 | Copper Tin Alloy |

| 0.00360 | Al Alloy (6201) |

| 0.00380 | Copper Silver Alloy |

| 0.00381 | Hard Drawn Copper |

| 0.00390 | Al Alloy (Al-59) |

| 0.00393 | Annealed Copper |

| 0.00400 | Al Alloy (STAL/TAL) |

| 0.00403 | Aluminium |

For small ΔT this linear correction is adequate. For larger ΔT or precision work, one must consider:

- α is temperature dependent. The single α value is an approximation valid near the reference temperature. For wide temperature ranges, higher-order terms (A, B coefficients for RTDs or polynomial fits) or tabulated values are needed.

- Material variability. α depends on composition, cold work, annealing, and impurities. Manufacturer datasheets or calibration certificates should be used when high accuracy is needed.

- Thermal gradients / self-heating. Measurement currents cause self-heating of the specimen, changing its temperature locally; for low-resistance measurements, use four-wire techniques, keep currents low for calibration checks, or apply corrections for heating.

- Thermoelectric (Seebeck) voltages. When dissimilar metals join (e.g., test leads to specimen), thermoelectric EMFs can bias low-resistance measurements. Use symmetrical current reversal, proper lead materials, or guard circuits to mitigate.

- Instrument ATC. Many commercial low-resistance meters offer ATC for copper or user-defined α. But ATC assumes the user chooses the correct α for the material under test (e.g., copper for conductor cores). Using the wrong α introduces systematic errors.

9. Practical recommendations for engineers and labs

- Always report the reference temperature. When publishing R values, state explicitly “R at 20 °C” (or “R20”) and the α used if a corrected value was produced.

- Use the right α for the material. Don’t assume copper α when measuring copper-clad alloys, brazed joints or alloyed conductors — check composition or calibrate against a standard.

- For precision lab work, use calibrated reference resistors. Buying a certified standard (with a calibration certificate and specified TCR) is better than relying on handbook α values.

- Use four-wire measurement for low resistances and minimize self-heating by limiting measurement current or by accounting for temperature rise.

- Document uncertainty. Include the uncertainty contribution from temperature correction (uncertainty in temperature measurement, uncertainty in α, possible nonlinear behavior) in your measurement report.

- For field/conductor testing, consider ATC but verify α. Many cable testers correct measured resistance to R20 using an internal α (commonly copper). For mixed-metal cable assemblies, this may be inappropriate.

10. Why this matters for Maxwell India readers (applications)

For companies and labs working with cables, connectors, shunts, and test equipment (the typical Maxwell India audience), the practical impacts are:

- Cable resistance specs are temperature-dependent. When you quote a conductor resistance per km or use resistance to infer conductor cross-section, state the reference temperature (often 20 °C). A cable measured in a 35 °C environment will have a measurably higher resistance than its R20 spec.

- Contact resistance and micro-ohm measurements: In low-resistance tests, slight temperature differences and lead thermoelectric voltages are often the dominant error sources — selecting correct α and applying precise correction to 20 °C is essential for traceable measurements.

- Designing shunts and precision resistors: Choose alloys (manganin, constantan) for low TCR to reduce drift and keep calibration intervals long.

11. Closing — the core idea in one sentence

Different α values exist because materials conduct electricity in different ways, and alloys let engineers tailor temperature behaviour — reporting resistance at a standardized reference temperature (usually 20 °C) ensures measurements are comparable and traceable across labs and standards.

References & further reading

- HyperPhysics — Resistivity & temperature coefficients (materials table).

- IEC 60751 — Platinum resistance thermometers (RTDs) and tolerance classes.

- ASTM B193 and other ASTM methods — resistivity and reference temperature practice (discusses copper α at 20 °C).

- Manganin (properties and near-zero TCR) — overview and historical use as a standard resistor alloy.

- Seaward Guide to Low Resistance Measurement — practical advice on ATC and R20 correction.

- IS 3636 — Indian method for temperature coefficient measurement.